The Smackdown

Lost at sea.

Lost in space.

Adrift alone in a vast ocean, the helpless victim of a freak accident.

Adrift alone in the cosmos… same dealio.

Man vs. Nature.

Woman vs. Nature.

One of the top movie stars of the ’70s, holding the screen all by himself for an entire film.

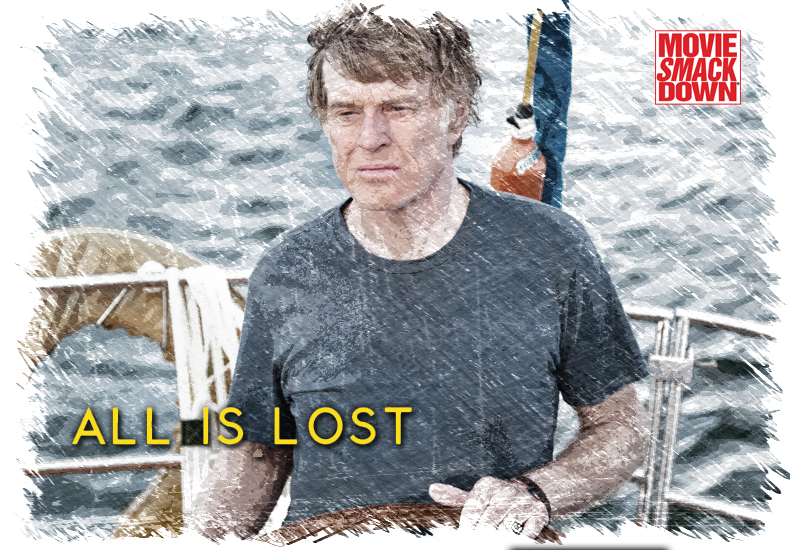

One of the top movie stars of the last 20 years, holding the screen all by her… well, okay, she’s got help, so we’ll stop there, but the point is, these two thematically similar movies of survival are facing off at your local cineplex as we speak. One is a studio blockbuster on its way to being among the year’s biggest hits, the other is a modest indie seeking sleeper success, and both seem destined for Oscar attention and rivalry, but in the meantime, let’s sit back and watch Gravity and All is Lost duke it out, keeping in mind that here at Smackdown, movie titles are not necessarily spoilers.

The Challenger:

The Challenger:

Our Man (Robert Redford, astonishingly well-preserved at 77) (and yes, that’s really how the credits list the character) is on a solitary ocean voyage on his yacht when he wakens to find that a collision with a stray shipping container has torn a hole in his boat and caused irreparable water damage to his navigation equipment and radio. His reaction is impressively stoic and rational; he handily patches the hole, but as the days pass and neither land nor passerby is in sight, his situation grows increasingly dire.

A storm hits. The boat leaks. He transfers to a life raft. Food and water run out. And then it really gets bad.

All this unfolds with barely a word of dialogue, a startling change of pace for writer-director J.C. Chandor, whose 2011 debut Margin Call was an economic horror story with an ensemble cast and nearly constant dialogue. (And, oddly enough, Demi Moore. Remember when her husband was being offered a million dollars to sleep with her by none other than… Robert Redford?)

The Defending Champion:

In Alfonso Cuaron’s Gravity, Dr. Ryan Stone (Sandra Bullock) is on her first space shuttle mission, outside the ship to work on the Hubble Telescope while avuncular Matt Kowalski (George Clooney) space-strolls around her, chatting with mission control as he attempts to break the long-standing space-walk duration record.

Houston (a welcome vocal cameo by Apollo 13 veteran Ed Harris) informs them that some stray debris from a Russian satellite is floating their way, and before Kowalski can even respond that yes, they do indeed have a problem, the ship is heavily damaged by the debris on impact, killing their other crew member and leaving the remaining two afloat and tethered together.

Their only chance of survival is making it to the International Space Station, but it’s a dual race against time as Stone’s oxygen runs low and another wave of debris is on its way. As the cool, confident Kowalski keeps the panicked Stone calm with flirtatious small talk, wisecracks, and the irresistible Clooneyesque panache, we learn of the tragedy in Stone’s recent past that she must ultimately work through if she’s going to survive the disaster.

The Scorecard:

If we put this in terms of a party metaphor: One is the guest whom you can’t help but gravitate (ahem) toward, drawn by her dazzling appearance and undeniable charm; the other is the quiet, brooding wallflower who you gradually realize, after patiently making the effort to draw him out, is the most fascinating dude in the room. Two wildly different animals, both well worth getting to know, but for nearly opposite reasons.

Yes, you should see both films. (Hell, you’ve probably already seen Gravity, quite possibly more than once. You might even be watching it right now.) Both of them tap into very basic universal fears of being stranded, helpless and alone. Both are testaments to the strength and resourcefulness in the face of danger and failing technology. Both are anchored by strong performances (shoo-ins for Oscar nominations), albeit of nearly polar opposite characters: Bullock wears all her angst, worry and personal baggage on her astronaut suit sleeve; Redford internalizes everything, until finally uttering what may be the most well-earned expletive in cinema history. And both films do a superb job of capturing their respective milieus, with Gravity being arguably the most convincing cinematic recreation of outer space since 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and All is Lost gorgeously depicting the overwhelming, and ultimately terrifying, vastness of the high seas.

The big differences here, aside from the obvious ones of setting and genre, are ones of tone, style and rhythm. Gravity is an exhilarating but herky-jerky and sluggish ride. It has a bravura opening sequence that establishes the characters and then briskly thrusts them into grave danger, seemingly all in one of Cuaron’s signature long takes. And other equally hair-raising episodes follow, but between them are stretches of flat-out boredom, crammed with incessant banter (written by the director and his son Jonas), familiar characterizations (Clooney, for better or worse, is at his absolute Clooniest), and constant technical updates (Bullock spends the first half of the movie reminding us of her steadily decreasing oxygen level). From beginning to end, the movie is a visual feast (gloriously filmed by brilliant Cuaron regular Emmanuel Lubezki) and an ante-upper in visual effects, but the script is disappointingly simple and hollow. Such a magnificent-looking movie deserves better dialogue and character obstacles than Kowalski advising Stone regarding her recent family tragedy, “You have to learn to let go.†(Dude. She went into space. Does it get much more “let go†than that?) Yes, obviously, the characters and dialogue aren’t meant to be the draw, but the point is, the movie’s best sequences are so good, so visually thrilling and intense and downright beautiful that the script’s shortcomings don’t quite torpedo them but knock the film down a peg so that it will be remembered as grade-A eye candy and not the rare Hollywood masterpiece it could have been.

All is Lost, by contrast, is brooding and contemplative. Its first half is so deliberate, it could understandably test the patience of some viewers, but as Our Man’s resources, options and chance of survival start to dwindle, the tension gradually ratchets up to a nearly unbearable degree. Has any film role in recent memory carried more formidable demands for its performer? Redford not only has to hold the screen by himself for the film’s entire 110-minute length, but do so without (practically) any dialogue or character background, using simply the emotions conveyed by his weathered (but still startlingly handsome) face. It’s an astonishing performance that instantly provokes reconsideration of the man and his entire career. It’s that good.

Cuaron, whose best film, by far, remains the Mexican menage a trois road comedy Y Tu Mama Tambien (2001), certainly deserves all the kudos he’s getting for what he accomplished visually with Gravity, for taking space-movie special effects to the next level, and for proving that even big-budget blockbusters can appeal to emotions and not just the primal desire of teenage boys to see stuff explode and vehicles go fast. I just wish it had taken a page out of Chandor’s book and trusted silence and subtlety and the power of its actor’s faces a bit more. Both films are, boiled down to their essence, simple tales of survival; the difference is that the more we learn about the characters in Gravity, the simpler they get, and consequently, the harder they are to care about; whereas we know next to nothing about Our Man, yet we come to care about him deeply. Not saying Gravity should have been as silent as All is Lost, but then again… how cool would that have been?

The Decision:

Far be it from me to try to dissuade you from seeing Gravity, if you haven’t already, which, in any case, is unlikely. By all means, see it in the theaters while you can, and in 3-D if you can. But ultimately, that’s all it is. Its pleasures, though eye-popping, are fleeting and superficial, and its script needed another pass, perhaps from the multi-talented J.C. Chandor. His dialogue-heavy Margin Call was my favorite film of 2011, and now with this one, he has proven equal facility as a writer-director of a dialogue-free film. And thus, because he had the audacity to make a film this unusual and risky, and the courage to trust hefting the weight of it onto Redford’s shoulders, and because Redford himself gives the performance of the year, the Smackdown trophy goes to All is Lost. We expect both films to garner many more trophies in the coming months.

Leave a Reply