The Smackdown

A successful, charismatic, well-spoken, African American man accompanies his white girlfriend to her parents’ home to meet her parents for the first time. What could possibly go wrong?

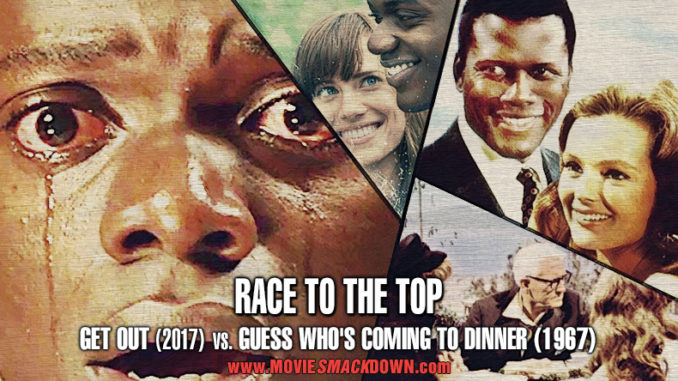

A lot, according to the competitors in today’s Smackdown, and in two very different ways. Our face-off pits this year’s huge sleeper hit, the creepy, suspense-satire Get Out, against its spiritual forefather from another cinematic era, the Oscar-winning, groundbreaking drama Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, which premiered half a century ago this year.

Will Get Out get out alive? Or will the Tracy-Hepburn-Poitier classic have it for dinner? We haven’t seen this kind of intergenerational battle royale since Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader locked light-sabers to see who got to sit at the head of the family table. So sit back and enjoy as we pit the edgiest hit, interracial film of today with one that held the title long ago in a galaxy seemingly far, far away.

The Challenger

Charming black photographer Chris (British-born Daniel Kaluuya) warily agrees to join his white gal-pal Rose (Allison Williams, on a break from Girls) to spend a weekend with her parents, Dean and Missy (the ever-invaluable Bradley Whitford and Catherine Keener) at their suburban estate, trusting Rose’s assurances that they’ll have no issue with his race, and ignoring the warnings of his conspiracy-spouting best friend Rod (an uproarious Lil Rel Howery).

Rose’s family turns out to be indeed quite welcoming, if a bit awkward around Chris, but telltale signs that something isn’t quite right about this gang keep popping up: The house’s black servants are all eerily mechanical and fake-sounding; Rose’s brother Jeremy (Caleb Landry Jones) gets oddly confrontational; and a hypnosis session with Missy takes him into bizarre, nightmarish realms.

To reveal more would risk major spoilage, but suffice it to say, the title supplies good advice for Chris.

The Defending Champion

The Defending Champion

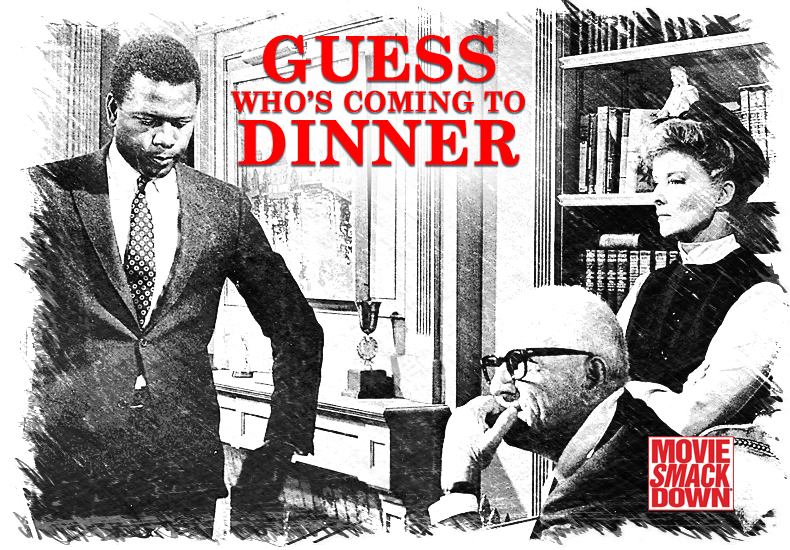

Spunky young Joey Drayton (Katharine Houghton) is so head-over-heels in love with her new fiancé, handsome doctor/humanitarian/widower/all-around perfect guy John Prentice (Sidney Poitier), that she just can’t wait for him to meet her parents, Christina and Matt (legendary Hollywood couple Katharine Hepburn and, in his final film role, Spencer Tracy) at their San Francisco home. She’s not worried in the slightest about how her seemingly liberal folks will react to the new beau, but his nervousness about the meeting is indeed warranted.

The parents are indeed thrown off kilter at first, then quickly calmed by John’s obvious intelligence, decency and genuine love for their daughter. Still, they want an easy life for Joey and have concerns about how the rest of society will react to her relationship.

John assures Matt he won’t marry Joey without parental approval, but distracting Matt from this weighty decision is the impromptu inclusion of additional dinner guests, including John’s equally startled parents (Roy Glenn and Beah Richards) and the cheerfully tolerant and tipsy Monsignor Ryan (Cecil Kellaway). The critical and commercial success of the film would go on to permanently shatter Hollywood’s interracial romance taboo, change movie marketing strategies forever, and garner a swath of Oscar nominations (including wins for Hepburn and screenwriter William Rose).

The Scorecard

Surely it’s no accident on the part of Jordan Peele (best known as half of beloved sketch comedy team Key & Peele, and making his writing/directing debut) that Get Out has a setup that all but Xeroxes GWCTD’s, only to gradually reveal itself to be its exact opposite in every other sense. Where one is sedate, static, and quaintly stagey, the other is increasingly suspenseful, creepy, raucously funny and crammed with wild twists and reveals. One is upbeat and hopeful about racial progress in America, the other bemoans its current state and depicts a world of ugly retrogression. One is about white people whose seemingly tolerant views are put to the ultimate test; the other is about white people who have shed the prior generation’s intolerance in favor of racial envy and taken it to pathological new heights. One is a talky polemic and, by today’s standards, pretty square (par for the course for director Stanley Kramer, king of the ’60s “message moviesâ€); the other is kinetic and visually inventive, steadily ratcheting up the tension and building to an action-packed climax.

So yes, the Peele film is in many ways, a clever, ultra-hip updating and subversion of its stodgy predecessor, but as stiff as it may play today, Kramer’s is the truly groundbreaking work of art. America in 1967 simply hadn’t seen interracial couples on screen before, much less treated (eventually) with such acceptance and positivity. Miscegenation was still (as one character mentions) illegal in several states during its production (the Loving decision resolving the issue would precede its release by six months); a year later, Captain Kirk and Lt. Uhura would debut interracial smooching on the small screen. Dinner was a daring, courageous movie in its day, probably made possible only by the participation of legendary actors Hepburn and Tracy and the impeccable, flawless image of (the soon-to-be-legendary) Poitier.

All of which accounts for the film’s towering reputation and importance, but all that aside, when viewed today, is it actually, you know, any good?

Well… let’s concede that to most modern eyes, it will probably come off as a bit hokey and didactic. The characters are drawn with fairly broad brushes (e.g. the impossibly perky Joey, the cartoonishly saintly John, the wise and twinkly-eyed, tippling Monsignor, etc.). Rose’s Oscar-winning script, which beat out, among others, Bonnie & Clyde (cue eye-rolls), is largely on-the-nose and devoid of nuance, and even the occasional attempt at metaphor -– Matt reluctantly tastes a new flavor of sherbet and is surprised how much he likes it –- play rather heavy-handed. But the lovely, noble performances by the ensemble cast (Tracy, Kellaway, Richards and Hepburn all nabbed nominations, with the latter winning her third) make it sing, with Tracy (in his last, illness-plagued days) delivering a final monologue so moving and poignant, it brings all his fellow cast-members to genuine tears.

Get Out, a wildly fun, exciting, laugh-filled, terrifying and even thought-provoking thrill ride, has a decidedly different feel. Peele’s film has been largely described as a horror-comedy, but the “horror†label doesn’t really fit; there are a handful of jump-scares sprinkled throughout, but the goings-on are really more sci-fi than horror, and in truth, the movie is too damn funny to really qualify as scary. Among other things, it’s a comedy of manners, a delightful, only barely exaggerated depiction of how awkward and unwittingly inappropriate white people can be around black people. This is never more apparent than among those, like the parents in both movies, who go overboard demonstrating their approval (such as when Dean assures Chris, immediately and unprompted, that he would have voted for Obama a third time). Peele’s smart, witty dialogue and razor-sharp direction, a commanding leading performance from Kaluuya and delightful ones by Whitford, Keener, and especially Howery, and solid technical work all around combine to make Get Out the first must-see movie of 2017 and one of the more impressive writing-directing debuts in recent memory.

The Decision

Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner’s message of tolerance was a significant step forward for progress and equality, on top of which the film showcases masterful acting by three screen legends at their best. Peele’s film, in its off-kilter way, is equally compelling. Will people remember it as a classic 50 years from now? Maybe not, but today it’s far more gut-busting, armrest-gripping fun. Which is why we salute Dinner with one hand, while with the other, we enthusiastically give Get Out the Smackdown trophy.

Leave a Reply