The Smackdown

The Smackdown

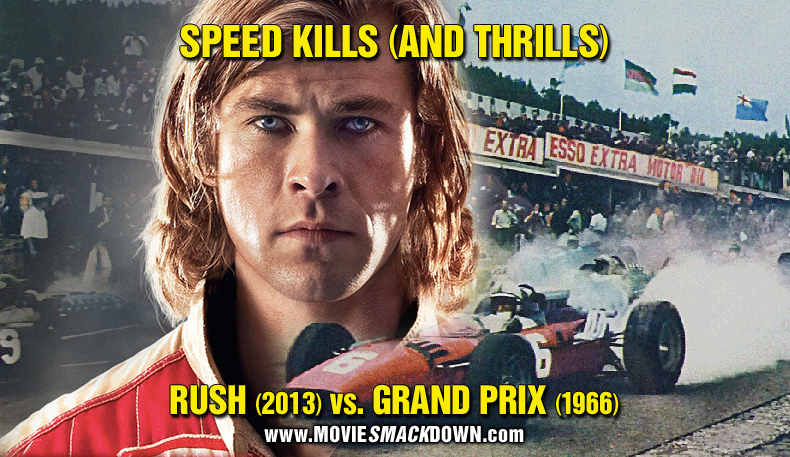

If there’s anything more viscerally exciting than watching Formula 1 auto racing, it’s got to be seeing a great movie about Formula 1 auto racing. The thrill of victory, the agony of premature hearing loss – it’s all there, along with the life-threatening danger, the prestige, and the beautiful women lurking like speed-bumps behind every hairpin turn.

Trouble is, making a great film on this subject is an extremely challenging enterprise. For one thing, F1 is relatively unknown in the United States. There have been very few American drivers, and all of the exotic, outrageously expensive cars are made overseas. For decades, the gold standard for auto racing films was set by visionary director John Frankenheimer’s Grand Prix, which follows a fictional set of characters during the 1967 F1 season and which thrust James Garner’s impressive early career to an even higher level.

With the maturation of computer graphics and the changing economics of the movie business, which depends more and more on overseas box office, director Ron Howard’s Rush is poised to challenge Grand Prix‘s 45-year lead on the Smackdown track. Can Howard’s brand new, true story Rush score the victory? Or does James Garner’s fictional battle for the F1 Championship still have the winning formula?

The Challenger

Two-time Academy Award-winning director Howard teams with two-time winning screenwriter Peter Morgan to present a spectacular big-screen re-creation of the 1976 F1 season, focusing on the sport’s two leading drivers at the time, James Hunt (Chris Hemsworth) and Niki Lauda (Daniel Brühl). Morgan’s script also pays ample attention to the sizzling trifecta of women in their lives – Gemma (Natalie Dormer), a nurse who knows how to dispense formalities along with her medicine; Suzy (Olivia Wilde), Hunt’s drop-dead gorgeous first wife; and Marlene (Alexandra Maria Lara), Lauda’s refined and faithful wife of fifteen years, a soul mate whose loyalty and devotion to a difficult husband may be equaled only by that of Sharon Osbourne.

The events of this historic season reach a flashpoint, literally, with Lauda’s horrific crash in the German Grand Prix at Nurburgring, leaving him extremely close to death, with a severely burned face and lungs. Confined for weeks to intensive care, Lauda watches Hunt continue to win and challenge his once insurmountable lead for the season championship. Driven to heal by his world-class competitive nature, Lauda makes an inspirational and astonishing return to racing, which climaxes at the final rain-swept event in Japan.

Bolstered by the use of high-quality, compact digital cameras, Howard and cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle deliver heart-pounding action sequences that put the audience in the stands and in the race cars themselves. It’s a hell of a ride, and it makes Rush a powerful, engaging and highly entertaining movie.

The Defending Champion

The Defending Champion

Oscar-winning screenwriter (All That Jazz) Robert Alan Aurthur’s fictional script focuses on the top four drivers during the 1967 F1 season, both on and off the track. Behind the wheel we find Pete Aron (Garner), an American who loses his ride, only to be hired for the final few races by a wealthy Japanese industrialist (Toshiro Mifune), who desperately wants his car to win its first F1 race. The reigning world champion is Jean-Pierre Sarti (Yves Montand), a Frenchman who is the leader of the legendary Scuderia Ferrari team.

Providing additional competition are the Englishman Scott Stoddard (Brian Bedford) and Sarti’s young teammate, Nino Barlini (Antonio Sabato, in his first English-language screen role). Behind the bedroom door we find three beautiful but dispassionate women – Louise (Eva Marie Saint), a cold American journalist who gets involved with the married Sarti; Pat (Jessica Walter), Scott’s high-maintenance, self-centered wife; and Lisa (Francoise Hardy), Nino’s latest nubile squeeze.

Shot in 70 mm six-track Super Panavision and released in Cinerama, Grand Prix is one film that truly utilized all of the state-of-the-art production techniques of the day. Sitting in front of a theater screen more than 100 feet wide, audiences literally felt the exhilarating speed and the ear-shattering sounds of high revving, 400-plus horsepower engines. Grand Prix comes as close as the average person will get to experiencing the inherent danger present on every lap, every turn of an actual F1 race. (Of the 32 drivers who participated or were seen in the film, five died in racing accidents within the next two years and another five in the following ten years.)

The Scorecard

In terms of script, Rush has the advantage of being based on a true story. Lauda was, by all accounts a cold, arrogant, calculating Austrian obsessed to be the best. The flamboyant Hunt was a highly charismatic, reckless playboy whose lifestyle included lots of booze, drugs and women (he is said to have had sexual relations with an NBA-worthy 5,000 of them before dying of a heart attack at 45). These two bigger-than-life, divergent personalities, each desperately seeking to become the premier global name in F1 racing, are captured perfectly in the complex, insightful screenplay by Peter Morgan who has a history of pitting head-to-head, real-life, powerful personalities, including the Howard-directed Frost/Nixon. By contrast, Aurthur’s Grand Prix script often plays as little more than an extended soap opera, leaving the heavy lifting to its thrilling action sequences and excellent cast.

But Rush‘s cast, too, is more than up for the job. Lauda and Hunt are compellingly portrayed by the remarkable Brühl and Hemsworth. Lauda’s story is one of unparalleled dedication, perseverance and outright will power. Audiences come to love Hunt as the dazzling, dashing dandy he is, but it is Lauda’s vulnerability and bravery that will resonate deeper and longer. There are no villains here, only two remarkable, highly talented, highly motivated adversaries who are not as black-and-white as the checkered flag found at the finish line.

While the off-track scenes provide an insightful, captivating look at the behind-the-scenes lives of two historic racers, Rush will also be remembered for its exhilarating on-track footage. One must assume that Howard screened Grand Prix prior to undertaking this project; his challenge is to at least equal, if not exceed, the cinematic spectacle brilliantly brought to the screen by our champion. With no CGI yet in existence, Frankenheimer used every Super Panavision camera he could get his hands on, the ultra-wide screen images benefitted from his occasional use of split-screen (in part to overcome the inherent distortion problems presented by Cinerama in close-ups). Just as impressive was Maurice Jarre’s captivating score, punctuated by the meticulously rendered, ear-splitting sounds of the various race cars. Howard gets close to surpassing this technical perfection, if not all the way there. Rush cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle, deserves much of the credit for that, especially for mounting so many of his three dozen digital cameras inside the race cars, providing a staggering visual immediacy. The extreme close-up of Hunt’s eyes behind the wheel captures the incredible focus needed to pilot a 180 mph F1 car as well as any camera technique previously employed. And the overhead shots of the blazing inferno engulfing Lauda’s blood-red Ferrari will not easily be forgotten.

These images are enhanced by the cello-driven score by Hans Zimmer, providing a surprising and unique counterpart to the speed of the cars and the sound of their screaming F1 engines. Additional kudos go to editors Daniel P. Hanley and Mike Hill who manage to condense a complex, multi-faceted story into a 123-minute running time, chopping nearly half an hour from Grand Prix‘s epic length. Howard and his team win that lap.

The best parts in Grand Prix didn’t go to the actors but to the cars, and when the action moves from off-track melodrama to on-the-track mega-drama, our Champion’s fortunes take a bigger turn than the famous Grand Hotel hairpin curve at Monaco, thanks to director Frankenheimer’s outstanding directorial, editorial and technical achievements when the pedal hits the metal. This film was a beloved favorite of countless young stoners, who typically sat mesmerized in their theater’s first row through repeated screenings. Now that, my friends, was a hell of a rush in 1967.

The Decision

Decision time – which of these two highly talented filmmakers brings home the Smackdown trophy? Grand Prix earns points for being a monumental technical achievement of its time, but Rush, too, excels there. Grand Prix is bigger and louder (not to be confused with Lauda). But Rush is faster, hotter, and ultimately better. Pop open the champagne, Mr. Howard. Our Smackdown winner, Rush, takes the checkered flag.

Very good article. I liked Rush, its a hard movie, but Grand Prix brings the romantic golden age of formula one. Loved the shots from this movie. We hold our breathe.

I was lucky enough to see both movies in the theater, & yes I saw Grand Prix in it’s original glorious Cinerama. Plus I followed the 1976 F1 season avidly through the reporting of Rob Walker in Road & Track magazine, as well as reading much more on it, so I’ve been intimately familiar with it for almost 40 years.

With all that background, as well as being something of a cineaste, I have a hard time deciding which is the better film. Rush is superior in plot to Grand Prix, which tends to wallow in soap suds whenever the action moves away from the track. The poorly written love triangle between Pete Aron, Pat Stoddard & Scott Stoddard should have been jettisoned from the script before filming started, & Françoise Hardy’s “acting” isn’t the stuff of awards, but at least her character’s relationship with Antonio Sabà to, Sr’s character of racer Nino Barlini has more of a ring of authenticity than the triangle I mentioned. The affair between Jean-Pierre Sarti & Louise Frederickson is also handled excellently, with two middle aged actors actually being given roles as lovers to play upon, & both Yves Montand & Eva Marie Saint play them to perfection.

Racing scenes: I have to give Grand Prix the nod here, because it not only captures a time that can never exist again, (as does Rush), but it captures it in a way that will never happen again either, & therein lies the difference. I have nothing against how well Rush does in this regard & fully understand & appreciate the need for & use of CGI in capturing an era that is itself long gone for contemporary audiences. Rush’s use of CGI is also far more realistic & superior to that used in another racing movie, Driven, as well as being superior to the non CGI racing footage in another racing movie, Days Of Thunder. Still, compared to the racing scenes in Grand Prix or Le Mans, Rush falls just a bit short for me, & this largely due to the currently popular use of quick cutting, dizzying camera work & a rapid fire technique. Some better tracking & establishing shots in the racing scenes themselves would have made all the difference there.

The acting in either film simply can’t be faulted, (with the aforementioned exception of Ms Hardy), but I think I prefer the portrayal of secondary characters such as Jeff Jordan & Izo Yamura in Grand Prix just a bit more overall. Daniel Brühl & Chris Hemsworth are superlative in their respective roles, but so are James Garner, Brian Bedford & Yves Montand in theirs.

The plot of Rush is admittedly better than that of Grand Prix & the shorter length is somewhat of a plus, but also somewhat of a handicap for Rush. Frankenheimer took three hours to tell several intertwining stories over the course of a single Formula One season, so even if the plot was sudsy, it at least had room & time to unspool & breathe. Rush crams six years of a racing rivalry into just two hours, which shortchanges some of the story. No mention is made of James Hunt’s first F1 victory in the Hesketh at the non championship BRDC International Trophy in 1974, or his first championship race F1 win in the Hesketh at the 1975 Dutch Grand Prix. About another 15-30 minutes added to the film would have told the story a lot better I feel, & kept it from feeling so “rushed”. They hit the highlights relatively well in the plot, & the acting of the main characters as well as Ron Howard’s directing pulls us through the gaps. So while the plot of Rush is better, the plot of Grand Prix is told better, because of that, & that makes a difference.

All told, I feel that Rush is the best film ever made about racing, but it’s not the best racing film ever made, & there is a difference. My personal choice for best racing film ever made isn’t Grand Prix either, No, that distinction still lies with Steve McQueen’s brilliant fictional “documentary” Le Mans. All three movies however are the best racing movies ever made.

Excellent comments — I enjoyed reading your insight and observations. Always good to have a fellow F1 enthusiast’s perspective…

saw it and loved it…

I am really excited about this one. Thanks for the informative review.