The Smackdown

The Smackdown

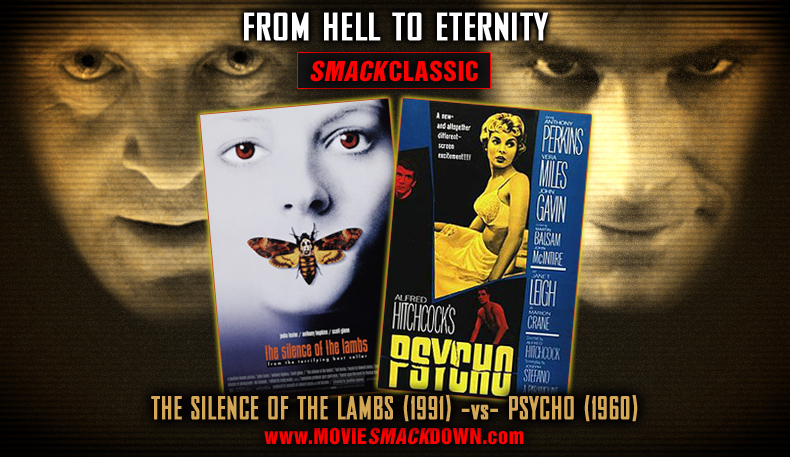

The horror, the horror. It’s Hannibal the Cannibal and Not-Yet-Agent Starling from the Oscar-sweeping Silence of the Lambs vs. Norman Bates and the Crane Sisters in the Hitchcock masterpiece that put the word Psycho into the pop vernacular.

In addition to their enduring popularity in film schools and on screens of all sizes, these two classics of high-end terror have an astonishing amount in common. One has creepy taxidermy, while the other has creepy butterflies. Both borrow elements from the crimes of real-life serial killer Ed Gein; both, based on popular novels, were departures of sorts for their directors; both feature female protagonists who become objects of judgmental and voyeuristic males. Both films deal with disturbing memories of a dead parent. Both set their climax in a killer’s cobwebbed basement. And both feature immortal villains played by actors named Anthony ___kins in unforgettable big-screen performances.

Oh yes, both also retain the power to make your skin crawl even after multiple viewings. So sit back and grab a glass of Chianti, because we’re about to dissect these two classics with a sharp kitchen knife, and only one will get out of this Smackdown alive.

The Challenger

The Challenger

Silence of the Lambs puts FBI agent-in-training Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster) on the trail of a serial killer nicknamed Buffalo Bill. To catch him, however, she must convince another serial killer, psychiatrist Hannibal Lecter to help her. The picture pulled off the rare feat of winning awards in all five of the major Oscar categories: Picture, Director (for Jonathan Demme), Screenplay (Ted Tally), Actress (Foster) and Actor (Anthony Hopkins). That a horror film achieved this made it all the more remarkable, given the Academy’s historical aversion to the genre (or it may speak to lack of compelling competition). Hopkins’ performance has become iconic; it is a safe bet that most of us had no idea what fava beans were before we heard him utter the phrase, and just as likely none of us will be cooking with them either.

Although he was not nominated, Ted Levine gives a courageous, unrelenting, utterly believable performance as Buffalo Bill. Somehow, Levine (who later found a home as Capt. Stottlemeyer on TV’s Monk) humanizes a serial killer without ever trying to make us like or understand him. Even in his gruesome depravity, there is more to connect with in him than there is in Lecter.

Lambs’ most enduring strengths are its stark realism and Levine’s performance. The creepy-scary factors of those elements outlast Hopkins’ histrionics and Foster’s woman-in-a-man’s-world courage.

The Defending Champion

The Defending Champion

It is almost impossible to watch Alfred Hitchcock and screenwriter Joseph Stefano’s Psycho with fresh eyes, given how much it has permeated popular culture (remember the band Bates Motel?), and become fodder for parody and serious criticism. Our fascination with it is such that the “Making of†documentary on the Special Edition DVD is longer than the film itself.

We are all aware of Psycho’s famous trick of killing off its lead character and most prominent actor before its halfway point, whereupon the narrative embarks on a whole new storyline, turning the stolen money into one of Hitchcock’s most celebrated Maguffins.

Psycho also oozes sex. The sweaty, post-coital passion and sharp dialogue of the opening scene gives way to a secretary (Pat Hitchcock, the director’s daughter) talking of taking tranquilizers on her wedding night and the flirtatious banter from a wealthy client. Even the tense exchanges between Marion and the Highway Patrolman and the Used Car Salesman have a latent sexual threat to them. Then there’s the white and then black lingerie we see Marion in on three separate occasions, all leading to the most famous shower of all time, where purifying sensuality abruptly gives way to shocking, naked helplessness. All of this is neatly foreshadowed when we hear Marion imagining the flirtatious client’s sudden change of tune: “If any of it is missing I’ll replace it with her fine soft flesh.”

Psycho’s climactic basement scene is as iconic in its scream-inducing terror as the shower scene. Yet not only is no one killed but the knife gets nowhere near a victim. It may be disappointing that Sam (John Gavin) comes in at the last instant to save the day, rather than allowing the Lila (Vera Miles) to defeat the villain on her own. Yet, as always, it is hard to argue with the drama of Hitchcock’s staging, and his brilliant economy when it comes to cinematic storytelling: It takes less than 30 seconds from the moment Lila opens the door to reveal the truth about Norman and his mother, but the first time you see it, it seems like forever.

Screenwriter Stefano changed Norman, who in the novel is forty, overweight and repellant, to make him younger, vulnerable and good-looking — someone an audience can sympathize with and not suspect as a murderer. He also brought out and legitimized the themes of mother attachment and sexual repression by making it a sore point in Marion and Sam’s affair and in the marriage of Pat Hitchcock’s secretary character, anticipating the more violent expression of it to come.

The Scorecard

It is a cliché truth that a horror movie is only as strong as its villain. Lambs novelist Thomas Harris’ greatest coup is realizing that the smartest, most capable person in the room is the monster we should fear the most. Hannibal Lecter is indeed the smartest person in the room, if not the world (although apparently not smart enough to avoid capture in the first place). He can decipher anything about anyone, and he has super-human senses, strength, self-discipline and will. That he uses those abilities for the most horrific, repellent evil, all while cruelly manipulating those around him, makes him more terrifying than any zombie or summer camp slasher.

Hopkins has a field day playing Lecter, showing off his considerable, um, chops, chewing celluloid much as Lecter chews his victims. He might as well be saying, I’m the fiercest actor in the world just as Lecter is the fiercest villain.

Perkins, on the other hand, never shows off and indulges in no winking or irony or telegraphing of guilt. Given how much Norman Bates is a part of our culture, it is difficult to appreciate what a truly great performance Perkins gives (at age 27). His Norman is sweet, nervous, and innocent, especially in comparison to Janet Leigh’s sensual if guilty confidence, Martin Balsam’s sharpness, and John Gavin’s physicality. Perkins’ anxious, candy-munching Norman is no match for any of them, and we genuinely feel for him (even if he is a Peeping Tom). Little do we know what lurks beneath Norman’s surface. It is only in the final moment of Norman alone in his cell when Perkins smoothly contorts his face into a mask of chilling malevolence that we glimpse the evil within. In contrast, there is little mystery to Hopkins’ Lecter: he is all surface. It is Ted Levine as Buffalo Bill in Lambs who makes the stronger challenge to Tony Perkins as Norman Bates.

Perkins’ shock and revulsion at discovering the shower death scene never for a moment gives away the truth. This is also a scene where Bernard Herrmann’s masterpiece of a score works wonders, just as much as it does during the murders. Turn the sound down during the scene of Norman cleaning up the bathroom, or earlier of Marion driving alone, and you will recognize the full dramatic power that music can bring to what is otherwise a static and downright boring sequence.

Psycho is one of the most genuinely frightening and blood-curdling movies of all time. Yet we see only two murders and we never see a knife actually touch skin. You may think you do, but you don’t. Lambs, on the other hand, sprays copious amounts of blood and other bodily fluids as well. Lecter and Bill emanate self-assured menace at every turn, while Norman Bates seems helpless and uneasy. Lambs even treats us to Lecter chewing on the face of a still-living victim, before flaying him in Grand Guignol fashion. It’s almost as if Demme were reliving his Roger Corman days.

Psycho’s move from the normal to the gothic – from the motel to the house – somehow makes sense. That menacing house may be a horror-movie cliché but it takes us so long to get there and we are so eager to learn the truth that’s inside, we accept it. Lambs is set in, and is at its best when it stays on, the disquieting margins of small town America, poor and close to the tracks, the same margins where the Bates Motel exists, far removed from the highway. Lambs begins to lose its hold, however, when Starling gets to the psychiatric ward where Lecter is held, a 19th century basement with ancient stone walls and a Count of Monte Cristo vibe. Given Lambs’ attention to gritty reality in its locations, costumes and visuals, the absurdly lax security surrounding Lecter after he is moved to an aging courthouse with two local guards strains credulity, as do the incompetent and ill-equipped SWAT and medical teams that respond to his inevitable escape. That may be the plot of the novel, but it doesn’t hold up on screen. Psycho’s post-climactic psychiatric explanation may be similarly far-fetched for our contemporary sensibilities, yet at least it takes Norman Bates seriously as a believable human being.

Lambs is even canny enough to recognize its debt to the reigning title holder: In Lecter’s storage area we glimpse a stuffed owl, its wings spread, that looks every bit as if it could be on Norman Bates’ wall.

The Decision

To dethrone a great champion, any challenger must be at the top of its game, without a single weak spot. Lambs has impressive strengths and lands powerful body blows to our fears. However, its conceits sometimes strain credulity, and its most famous, flashy performance is a bit over the top. There’s a reason Alfred Hitchcock was known as the Master of Suspense, and in Psycho, he and his team have created a classic that still reigns undefeated. This one doesn’t even go the distance: The pulpy terror of Psycho beats Silence of the Lambs to a bloody pulp.

I just watched both of these films back to back, along with Red Dragon. While Psycho is good, it is closer to Red Dragon; and directly comparable to that film.

I disagree, while Psycho is a great film, Silence of the Lambs is the superior of the two. It is perhaps the only suspense film to distance itself ahead of Hitchcock. If Hitchcock had survived, and (hypothetically) made Silence of the Lambs, there would be little doubt that it would be considered he greatest film in the history of movies to this day; reason being, films often lose points because many amateur critics tend to appeal to authority (such as Hitchcock)rather than examine the work of art for its own merit.

Silence of the Lambs is clearly the most entertaining. It’s a much more thrilling and interesting film to watch. All three films dabble in the black humour, and Silence not just beats the other two, but it bests any movie out there in all its details.

On a scene to scene basis, it’s clear that Silence of the Lambs borrows heavily from Hitchcock; especially Vertigo and Notorious, and probably Psycho as well – although I didn’t gather it quite as much. Silence delivers the Hitchcockian style masterfully.

Lastly, the plot and dialogue of Silence of the Lambs is just much better written. It dabbles heavily in the theatrics when it comes to Hannibal, and that’s his character; a gentleman psychopath who attempts to turn his entire life into a work of art. To penalize Silence for that, and the entire film because you think Hannibal’s character is wrong, because he doesn’t fit neatly into the archetype of Norman Bates, is a huge mistake. The Hannibal character is excellent, and far superior to Norman Bates.

In terms of which movie made the bigger splash for the time period, certainly Psycho. As for which is the best film in the genre, without a doubt it is Silence of the Lambs.

Psycho Is Better Than The Silence Of The Lambs.

Thanks for the thoughts, Rodney. I used to agree about Lambs, and certainly felt as you did when I first saw it. I was pleased when it won its awards. It has not aged well, in my opinion, even on its own and especially in close, comparative viewings against Psycho. Hopkins is a phenomenal actor, and his Lecter is certainly a great screen villain — this is a battle between classics, after all. It just doesn’t get to me the way it once did: I see the artifice, see Hopkins “working”. (Olivier, by his own admission, gave mediocre and terrible performances that were well-reviewed, as has Brando and, well, name a great actor.) I just don’t find Hopkins and Lambs as deeply compelling, or chilling, or mysterious, as I do Perkins and Psycho. In the end, of course, this is all subjective and we are attempting to analyze gut, instinctive reactions. As with attraction, it’s in the eye of the beholder — assuming one’s eye isn’t covered in fright. I do appreciate the response.

This Smack was always going to be hard to judge, because of the legacy both films created in their wake. It’s hard to argue with the Big Five Oscars that Silence snagged, if I was honest, and while I agree Psycho is still a giant in the genre, for sheer visceral chills, larger characters and more spine chilling cerebral intellect, I’d give the win to Silence of The Lambs. And to call Hopkins’ performance “over the top” and “flashy” is a little disingenuous – at least I hope you’re referring to Hopkins with that statement – since he’s easily regarded as one of the best screen villains of all time. It’s a lot closer battle than you give credit for.