The Smackdown

The Smackdown

I haven’t traveled widely, but from what I have gleaned at art houses and in history classes, both Germany and Russia have a certain recognizable something that distinguishes their native sons, an identifiable quirk of national character unmistakable and uniquely their own. While both films under consideration are up for Academy Awards, I’ll bet very few Smackdown readers have seen either one. I’ve braved the arthouse crowds and brought back this humble comparison intended to help you decide which nominated film is most worthy of your valuable time and attention. Creepy Germans versus Mad Russians. Bring it on.

In This Corner

In This Corner

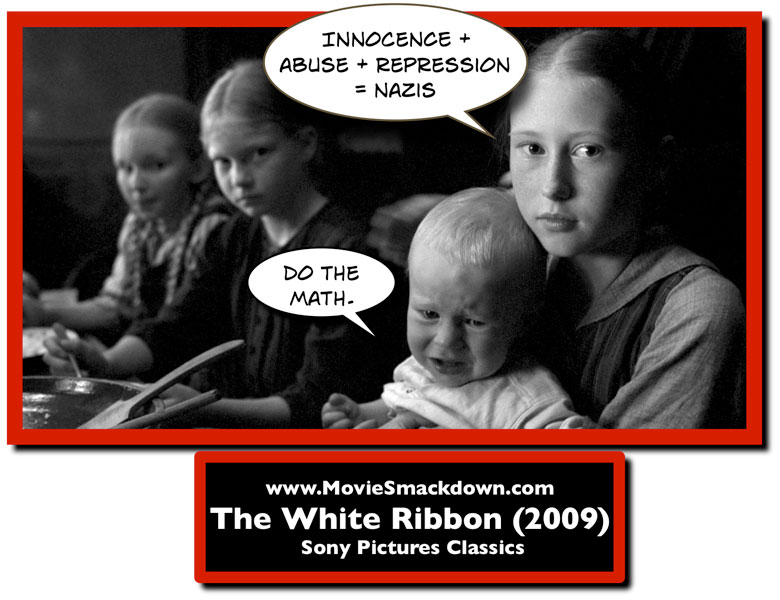

Over the fifteen months preceding thefir st world war, a series of increasingly strange events unfold in a tiny German town. (In this hamlet, something’s rotten in the state of Germany, not Denmark.) The denizens are not individual characters so much as monstrous archetypes; the landed baron a controlling overlord who gradually loses control, the doctor a cold, cruel, and sexually perverse father, the pastor sexually repressed and physically abusive to his many children, the schoolteacher ineffectual, romantic, and somewhat distracted. The children are beaten and tortured, molested and abandoned, mistreated and punished for every infraction. The women are muzzled, abused, and dispatched with not much fanfare. Even the crops suffer brutal beheadings, and the pets are savagely killed. In revenge, they act out their dark fantasies, traveling in a creepy Children-of-the- orn-style pack, walking in an ominously straight line, visiting mysterious cruelties on the different, the Other. All this ritualized punishment rains down on the entire town; initially, the town looks normal, but soon the bucolic vistas yield to a slow motion horror movie, all portent and unease.

In That Corner

In That Corner

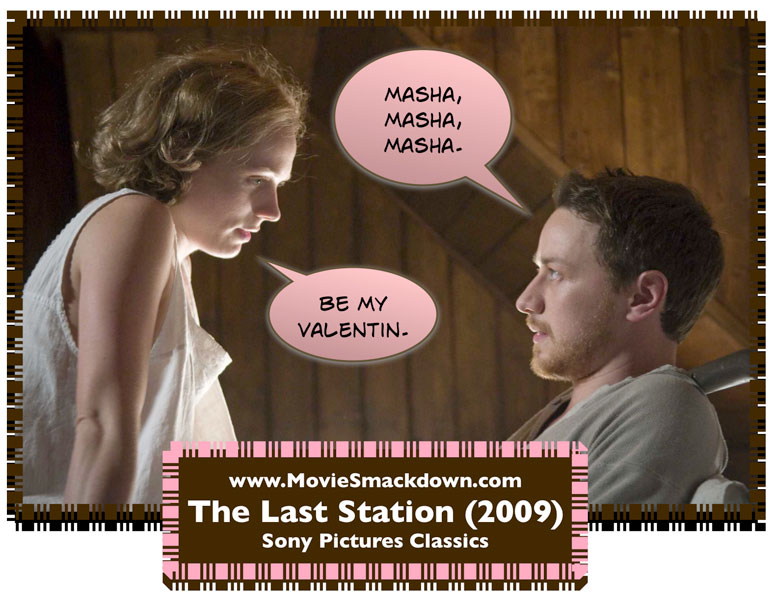

The last days of Leo Tolstoy provide a provocative setting for “The Last Station.” All the characters struggle for Tolstoy’s affection and approval; as the Great Man nears death, a contest of wills erupts and explodes, focusing on his hotly contested will. Tolstoy’s wife and muse, the formidable Countess Sofya (Helen Mirren) battles Tolstoy acolyte Vladimir Chertkov (Paul Giamatti) over the rights to Tolstoy’s work and property. Politics and philosophy make for a fascinating screenplay. The squabble personifies the great Russian philosophical question of the early twentieth century – the preservation of personal property and security versus the pursuit of an anti- aterialistic, greater good. Tolstoy and his followers struggle to reject all material comforts and personal concerns – fame, wealth, even romantic love — and most of them fail in intriguing and telling ways.

The Scorecard

I’d characterize movie Germans this way; they seem to thrive under strict discipline, fostering domination and creating high achievers through regimentation and repression, control and remarkable reserve. Stiffly formal and resolutely uncomfortable with open emotional expression and release, movie Germans stoically stand and sit at attention, sticks planted firmly and rigidly supporting their spines.

Most post-war German films must deal somehow with the elephant in the room as all Germans must address the past and make some peace with all that warring. How did that nation conspire to exterminate millions? Asking “What did you do in the war, Daddy?” makes for some intriguing and involving cinema. Everyone over a certain age carries that historic burden, and all those born too late carry the national guilt uneasily. “The White Ribbon” poses a slightly different question with some very unsettling answers. This very creepy look at a highly dysfunctional little hamlet on the eve of the first world war shows us the children who grew up to be Nazis and asks us to examine up close and personal some of the factors that might have created such a secretive and sadistic generation.

The film is beautifully, if statically, photographed in murky black and white. The mood is somber and haunting; horrors lurk behind every closed door, and deaths occur often and without much ado. Proceeding at a snail’s pace, “The White Ribbon” challenges its audience with all that joyless slogging, but those who brave the two and a half hours of heaviosity will have much to discuss and analyze. Still, reading about it and thinking about it might prove more fun than actually watching it.

Movie Russians are very emotional, passionate and obsessed with words and big ideas – love and justice for instance. They argue operatically, hugging freely, laughing heartily, crying openly; these human hurricanes of feeling and philosophy are given to grand gestures and grander speechifying. “The Last Station” is not a foreign language film; no bogus Russian accents clutter the aural landscape. Brits and Americans alike do justice to an intelligent and emotionally affecting screenplay.

Featuring an award-worthy performance by Academy favorite Helen Mirren and a career-capping turn by Christopher Plummer as Tolstoy, writer-director Michael Hoffman draws terrifically lively performances from his entire cast. Mirren plays the countess as spitfire seductress, with brain and balls to boot. No tiptoe-ing into her dotage for this formidable dame. James McEvoy is particularly winning as Valentin, the young man who idolizes Tolstoy and comes to work for him. Most of the story unfolds through his innocent (and no-longer-innocent) eyes. The scenes of Valentin falling in love (and forbidden lust) with Masha (Kerry Condon) are filled with welcome warmth and humor. Tolstoy’s deathbed scene felt both historically accurate and emotionally relevant; somehow, through the veil of history, something universal and timeless shines through and overtakes us. Over the end credits, we are treated to actual silent footage of the real Tolstoy and his pigeonbreasted Countess; while Mirren cuts a decidedly more elegant figure, the period details and settings of the film ring true and resonate in the memory coupled with this rare documentary glimpse.

The Decision

“The White Ribbon” means to disturb and unsettle us; it accomplishes its goal almost too well. A slowly unfolding nightmare of unanswered mysteries and haunting images, it lingers long. “The Last Station” is a more rollicking adventure, filled with humor and big ideas. Its drama is leavened with comedy and recognizable family dynamics, and the performances are uniformly excellent. The locations too are exquisite; there are cinematic thrills to be had riding through those quintessentially Russian birch woods by carriage and arriving at a country estate in its last gasp of elegance and privilege. The winner: “The Last Station.”

Gotta say I’m in the minority and prefer The White Ribbon. Thought it was one of the best films of the year and a solid choice for at least best foreign.

McEvoy’s charms escaped me in his previous outings as well. I think you’ll be pleasantly surprised as I was.

I think THE LAST STATION is probably worth viewing if for no other reason than to see James McEvoy as “particularly winning” — something I have yet to actually dial in to. Fine Smack, though, and clearly Tolstoy seems the character to spend some time with.

I have seen both films and and am impressed with the Smackdown. I didn’t find The White Ribbon as bearable as you did, ( I hated it) but on reading the review I will concede the director’s intent. On the other hand I found The Last Station to be everything you say it is and more. A good movie as well as an impressive history lesson. Food for thought. Good stuff.